|

|

|

|

News, Information, Blogs

Whats News?? More to Read!

"History is a light

that illuminates the past, and a key that unlocks the door to the future."

--Runoko Rashidi

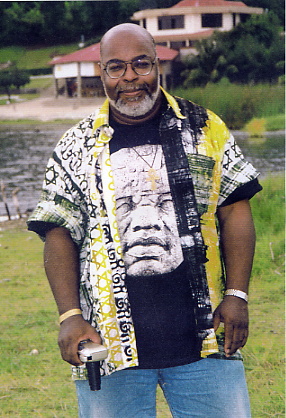

Runoko Rashidi is a historian, research specialist, writer, world traveler, and

public lecturer focusing on the African presence globally and the African foundations of world civilizations. He is particularly

drawn to the African presence in Asia, Australia, and the Pacific Islands, and has coordinated historic educational group

tours to India, Aboriginal Australia, the Fiji Islands and Southeast Asia as well as Egypt and Brazil.

In regards to the mass media, Runoko is much sought out for radio, television, and newspaper interviews, having

now been interviewed on more than 200 radio broadcasts and more than a hundred television programs. As a public lecturer,

during the past twenty years he has made major presentations at more than 125 colleges and universities and scores of public

and private schools, libraries and book stores, churches and community centers. On the international circuit he has lectured

in Australia, Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Canada, Columbia, Costa Rica, Egypt, England, Ethiopia, France,

Fiji, Germany, Guyana, Honduras, India, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Morocco, Myanmar, Namibia, the Netherlands,

Netherlands Antilles, Niger, Panama, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Thailand, Trinidad, Turkey, Uganda, Venezuela, Vietnam,

and Zimbabwe.

Rashidi's presentations are customized and suitable for all audiences and ages, and are lively, engaging,

and vividly illustrated.

Runoko is the author of Introduction to the Study of African Classical Civilizations (published by Karnak

House in London in 1993), the editor, along with Dr. Ivan Van Sertima of Rutgers University, of the African Presence in Early

Asia, considered "the most comprehensive volume on the subject yet produced" (published by Transaction Press, and now in its

third edition), and a major pamphlet titled the Global African Community: The African Presence in Asia, Australia and the

South Pacific (published by the Institute of Independent Education in 1994). In 1995, he completed editing Unchained African

Voices, a collection of poetry and prose by Death Row inmates at California's San Quentin maximum-security prison. In December

2005 Editions Monde Global released Runoko’s latest work and his first French language text, A Thousand Year History

of the African Presence in Asia.

Runoko Rashidi is a prolific writer and essayist. As an essayist and contributing writer, Runoko's articles

have appeared in more than seventy-five publications. His historical essays have been prominently featured in virtually all

of the critically acclaimed Journal of Civilizations anthologies edited by Dr. Ivan Van Sertima, and cover the broad spectrum

of the African presence globally. Rashidi's Journal of African Civilizations essays include: "African Goddesses: Mothers of

Civilization," "Ancient and Modern Britons," "The African Presence in Prehistoric America," "A Tribute to Dr. Chancellor James

Williams," "Ramses the Great: The Life and Times of a Bold Black Egyptian King," "The Moors in Antiquity," and the "Nile Valley

Presence in Asian Antiquity."

Included among the notable African scholars that Runoko has worked with and been influenced by are: John Henrik

Clarke, John G. Jackson, Yosef ben-Jochannan, Chancellor James Williams, Charles B. Copher, Edward Vivian Scobie, Ivan Van

Sertima, Asa G. Hilliard III, Obadele Williams, Charles S. Finch, James E. Brunson, Wayne B. Chandler, Legrand H. Clegg II,

and Jan Carew. He believes that his principle missions in life are to help make Africans proud of themselves, to help change

the way Africa is viewed in the world, and to help reunite a family of people that has been separated far too long.

As a scholar, Runoko Rashidi has been called the world's leading authority on the African presence in Asia.

Since 1986, he has worked actively with the Dalits (India's Black Untouchables). In 1987, he was a keynote speaker at the

first All-India Dalits Writer's Conference, held in Hyderabad, India, and spoke on the "Global Unity of African People." In

1998, he returned to India to lecture, study and sojourn with the Dalits and Adivasis (the indigenous people of India). In

1999, he led a group of seventeen African-Americans to India, and became the first ever non-Indian recipient of the prestigious

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Memorial Award.

On December 5, 2002 Runoko Rashidi was granted an honorary doctor of divinity degree by the Amen-Ra Theological

Seminary in Los Angeles, California.

Runoko Rashidi has dedicated his entire adult life to African people. For

additional information on educational tours, to schedule lectures, to purchase books, dvds, photos and more Runoko can be

easily reached via the Internet at runoko@yahoo.com, or call him at (210) 337-4405. You may write Runoko at Runoko Rashidi,

Box 201662, San Antonio, Texas 78220

For additional information on educational tours, to schedule lectures, purchase

audio and video tapes Runoko Rashidi can be easily reached via the Internet at runoko@yahoo.com, or call Runoko at (210) 648-5178.

You may write Runoko at Runoko Rashidi, Box 201662, San Antonio, Texas 78220

Runoko Rashidi is very active online. His most comprehensive and popular

web site, The Global African Presence, is brilliantly illustrated, regularly updated,

and designed and maintained by Kenneth Ritchards. The Global African Presence Web site may be visited at http://www.cwo.com/~lucumi/runoko.html

Copyright © 1998 Runoko Rashidi. All rights reserved.

Revised: March 13,

2006

|

| Runoko Rashidi |

Top 10 Black Myths!!

By Darryl James

One of the most glaring problems facing African Americans is the media’s love affair with Blacks, especially Black men.

They love having us on the news, but the coverage is largely relegated to perpetual poverty, crime and other “bad”

behavior. While we are neither the dominant nor the majority population, the negative media coverage is disproportionately

high when it comes to us.

Many of our other difficulties stem from

that poor media coverage, which leads many to believe that there are more of us doing bad things than there really are.

It also leads many to the belief that, accordingly, there are less of us doing good and positive things, except for those

laughing Negroes on UPN.

It is

no secret that African Americans have an image problem. It is also no secret that the media misrepresents African Americans.

What is ostensibly a secret is that many of the most egregious things being said about Black people are being perpetuated

by Black people.

In another

Black Top Ten list, I’d like to dispel some of those myths.

Accordingly,

these are the top ten things that Black people should stop saying about Black people:

The Top Ten Black Myths

1. There are more Black men in prison than in college.

False.

The numbers that people quote are ALL of the Black men in prison, versus ONLY the free young Black men of college age, which

spans the late teens to the early twenties. If a comparison of age range to age range is conducted, there are actually

more Black men in college of college age, than in prison, and of course, there are more Black men out of prison than in prison.

The misleading

“evidence” comes from studies such as the one conducted in 2000 by the

Justice Policy Institute (JPI), a Washington-based research group. JPI found that there were 791,600 Black men in jail

or prison and “only” 603,032 of them in colleges or universities. They also presented the findings as “evidence”

as that there were more Black men in prison than in college.

Any of us can do the math: Out of the 33.7 million African Americans that the 2000 census found, less than one million

are in jail or prison (.792 million).

The reality is that while there are too many of us in prison and more of us in there than others, there are NOT more

of us on the inside than on the outside.

2. Black people, particularly Black men are lazy.

False.

How can a people who built this nation and did it for free suddenly become the laziest people in the nation?

According

to the US Census Bureau, 68.1% of all Black men over the age of 16 are in the civilian labor force, compared to 73% of white

men. With racial discrimination and other challenges, more of us are still working than sitting at home.

Here’s

something else that’s interesting. According to the same stats from the US Census, 62.3% of Black women over the

age of 16 are working, while only 59.9% of white women are.

While

the majority of poor people in America are Black, the majority of Black people are NOT poor. Of the 33.7 million Blacks

in this nation, 8.1 million have incomes below the poverty line.

Now, what we do with our money is another story…

3. Black people abuse the Welfare system and are swelling it beyond capacity.

False.

First, the actual number of Black families on Welfare has been decreasing since the early 1970’s, when 46% of the recipients

were Black. By the end of the 20th century, that number was down to 39%, as compared to 38% whites who were non-Hispanic.

If the comparison were strictly based on race without ethnic identification, whites clearly outnumber Blacks on the Welfare

rolls.

In addition,

40% of the families on Welfare have only one child, while the number having five or more is only 4%. And, by the

last decade of the 20th century, Welfare accounted for just over 2% of the Federal Budget, while defense accounted

for 24%.

Benefit

programs for farmers and big businesses far outweigh the Welfare program. For example, US Airways was recently given

permission to tap into a $718 million federally guaranteed loan package to fund daily operations while in bankruptcy proceedings.

Who is abusing welfare?

4. Most Black men are married to white women.

False. As of 1998, interracial marriages

composed of a white person and a Black person accounted for only .6% of all marriages in the nation. Of all interracial marriages,

only 16% are Black male to white female.

5. Affirmative Action unfairly provides opportunities for Blacks.

False.

First, Affirmative Action is inappropriately used to define Black preferential treatment and “quotas” but it was

actually designed to benefit a number of groups who have been discriminated against, creating parity in the workplace.

Since the 1970’s, Affirmative Action has benefited white women more than any other group. Secondly, no one who perpetuates

this myth ever talks about other types of Affirmative Action, which benefit other races. For example, the Japanese descendants

in America, who were each rewarded $20,000 in 1988 as reparations for internment during WWII, or the legacy programs which

benefit people such as the current dimwit in the white house.

6. Let’s kill two ignorant rumors with the pursuit of truth: Poor Blacks would be better off if they stopped

using drugs and took better care of their communities; and, Blacks need to stop pushing drugs to their own people.

False. This one always

confuses me, because Blacks can’t even distribute their own movies or music, yet still get blamed for importing and

distributing ILLEGAL drugs. If a Black man can’t drive down the street without being racially profiled and stopped,

what makes anyone think that he could fly a planeload of drugs into the nation and distribute them from state to state and

city to city? The drug dealers in the ‘hood make a lot of money, but nowhere near the cash generated by the true

drug lords who import it and distribute it to inner cities across the nation.

7. Blacks suffer from Black on Black crime.

True,

but misleading. Whites also suffer from white on white crime. Many crimes, including murder, rape and robbery

are crimes of location, not color. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 85% of African Americans report another

Black person as the perpetrator of the crime and 80% of white murders were committed by other whites. However, when race does

play a role in crime, the victims of violent crimes are more likely to be Black, while the perpetrators, are more likely to

be white.

8. Blacks commit more

crimes than whites.

False.

Neo-Conservative Whites and self-hating Blacks notwithstanding, the reality of racism in the justice system has to be understood

in order to get into the reasons for the high number of Blacks in prison.

In an

assessment of the impact of crime on minority communities, the National Minority

Advisory Council on Criminal Justice concluded that “America is a classic example of heavy-handed use of state and private

power to control minorities and suppress their continuing opposition to the hegemony of white racist ideology.”

Further, according to “The Real War on Crime,” a report by the National Criminal Justice Commission, “African-American

arrest rates for drugs during the height of the ‘drug war’ in 1989 were five times higher than arrest rates for

whites even though whites and African-Americans were using drugs at the same rate.”

Finally, by 1990, according to the Federal Judicial Center, the average sentences for African Americans for weapons

and drug charges were 49% longer than for whites who had been convicted of the same crimes.

The simple

truth is, more of “us” may be in court, but more of “them” are actually committing crimes.

9. Women outnumbering men in college is a Black phenomenon.

False. According to the US Department of Education, male undergraduates account for 44 percent

of student population, while female undergraduates account for 56 percent. This is not race specific. There are

some real reasons for it and I will deal with it in an upcoming column.

10. Black people are incapable of sustaining businesses in their own communities.

False.

We had great success before integration. In fact, by 1900, the number of African-American businesses nationally, totaled 40,000,

including the Greenfield Bus Body Company, which manufactured automobiles, and a hotel in New York City valued at $75,000.

By 1908, we had 55 privately owned banks. By 1912, there were two millionaires, Madam C.J. Walker (hair care) and R. R. Church

(real estate).

By 1923, Tulsa, Oklahoma was home to The Black Wall Street, an African American community of 11,000. Which featured

nine hotels, nineteen restaurants and thirty-one grocery stores and meat markets, ten medical doctors, six lawyers, and five

real estate and loan insurance agencies, complete with five private planes.

|

|

|

Black and Male in America

By Kevin Powell

I read the recent New York Times cover

story, “Plight Deepens for Black Men, Studies Warn,” with a great deal of pain and sadness. As a Black man who

is in his late 30s, I have literally encountered every dilemma documented: I am the product of a single-mother led household,

fatherlessness, horrific poverty, omnipresent violence in and outside of the tenements of my youth, and the kind of hopelessness,

depression, and low self-esteem which led me to believe, very early on, that my world was just one big ghetto, that Black

boys like me were doomed to a prison stint or a premature death, that there was nothing we could do about it.

For sure,

much of my life has been spent attempting to both reconcile and ward off the demons of those circumstances. On the one hand

I managed to get to college on a financial aid package because my mother instilled in me, in spite of her possessing only

a grade-school education, a love of knowledge. But, by the same token, the cruel variables of my adolescent years followed

me into adulthood, leading to temper tantrums, arrests, suspension from college, job firings, and violent behavior toward

males and females which has only subsided in the past couple of years because of a renewed and determined commitment to therapy,

healing, self-love, and spiritual transformation. I have had a very productive career as a writer and I have been homeless

and hungry as a grown-up. I have traveled much of America lecturing and bringing people together, and I have burned more bridges

than I care to admit. And I have been a great model for Black male achievement to some, while a symbol of the worst aspects

of contemporary Black masculinity to others. It is not an easy balancing act, because most of us poorer, fatherless Black

males, especially, were not presented with a blueprint for manhood as boys, other than the most destructive forms in our 'hoods

and via popular culture. Thus we find ourselves stumbling through minefields riddled with systemic racism, classism, drugs,

guns, crime, gangs, minimal expectations, unprotected sex, disease, and death. We often have to figure this all out for ourselves,

with little guidance or direction. And we are, indeed, those homeboys you see on America's street corners, left alone to fester

and rot our lives away.

For me these days there is a foundation, a calling, which has led, the past half decade, to

my seeking solutions to this monumental crisis around Black manhood. I am brutally honest about every aspect of my life journey,

I highlight it in my writings, and I talk about it on college campuses, at prisons, in churches. I organized a ten-city State

of Black Men tour in 2004, and I have been a part of various think tanks, like the Twenty-First Century Foundation's initiative

on Black boys and Black men, in an effort to confront this catastrophe head-on. And I have placed my time and energies in

full support of anti-violence and anti-domestic violence programs locally and nationally. Without question, so much of American

maleness is rooted in the belief of White male superiority, patriarchy, sexism, homophobia, violence, materialism, and it

is abundantly clear how those stimuli disproportionately and disastrously affect poor Black males. Or, rather, what was said

in the New York Times article is accurate in each and every city I have visited: “We're pumping

out boys with no honest alternative.”

Part of the problem, undeniably, is perpetual governmental neglect at the

federal, state, and local levels. If a similar article had been written with the heading “Plight Deepens for White Men,

Studies Warn,” it would be considered a national emergency, monies would be earmarked for a domestic Marshall Plan focusing

on these White males, and empowerment policies would be implemented immediately. It is disturbing to say that, regardless

of all the hard fought victories of the Civil Rights Movement, we remain a nation profoundly damaged by racism and classism.

Little

wonder, then, that as I work with and talk to younger Black males in urban settings they aspire to be three things: a rapper,

an athlete, or some form of a street hustler. These limited life options exist because not only has governmental agencies

largely abandoned this population, but so too has the Black middle class, and, specifically, those of us who are Black male

professionals. It is a very obvious phenomenon to me: in segregated America, Blacks were forced to dwell in the same neighborhoods.

Thus even if you were a poor Black male, you at least saw, in your community on a regular basis, Black men with college degrees,

Black men who were doctors, lawyers, businessmen-Black men who offered a proactive alternative to the harsh realities of one's

poverty-stricken life. Integration not only brought about wholesale physical removal of the Black middle class, but also wholesale

emotional removal as well. A broken relationship, if you will, that has never been mended. This is the vacuum, the gaping

hole, for the record, that created hiphop culture, a predominantly poor Black and Latino male-initiated art form, in America's

ghettoes right on the heels of the Civil Rights era in the late 1960s, early 1970s. And this is why hiphop, to this day, with

its contradictions notwithstanding, remains the primary beacon of hope for poor African American males. I cannot begin to

count how many underprivileged Black males across the nation have said to me “Hiphop saved my life.” That speaks

volumes about what we as a society and as citizens are not doing to assist the less fortunate among us.

So as we rightfully

petition the government, on all levels, to work to improve the opportunities for poor Black males, to view this crisis surrounding

Black boys and Black men as linked to the very future and livelihood of America, I issue a challenge to professional, successful

Black males like myself: Become a breathing, living example for these poor Black boys and men. Share life lessons with them,

mentor them, please, and do not be afraid of them, ever. And have the courage, the vision, to be a surrogate father for one

younger Black male, particularly if you do not have children of your own, knowing that that very simple act may not only save

a life, but several lives. I personally advise, here in Brooklyn, New York where I reside, at least five younger Black males

on a consistent basis. No, it is not easy, but I feel I have an obligation to do so because I have been blessed to overcome

so many obstacles myself. And I have the basic responsibility, by being mad real with them, of showing and teaching these

younger boys to men how they can avoid all the mistakes I made. Yes, we must think as a community, not as selfish and nearsighted

individuals. And it is direct action that we need, and direct interaction as role models, as big brothers, if the tide is

going to be turned for Black boys and men.

In June 2007 a group of us will be producing, in New York City, a gathering

entitled Black Men in America…A National Conference. We will bring together Black male social workers, anti-violence

facilitators, spiritual and religious leaders, artists, athletes, psychologists, media insiders, elected officials, policymakers,

educators and scholars, grassroots activists, hiphop heads, the young and the old, for four critical days. The idea was conceived

because it is evident to Black men like me that there is a national movement happening to redefine Black manhood. There are

selfless, dedicated Black males struggling, throughout the United States and in the trenches on the daily, around this historic

crisis. They have names like Byron Hurt, Dr. Mark Anthony Neal, Dr. Jelani Cobb, Charlie Braxton, Ed Garnes, Brian Smith,

Robert Page, Thabiti Boone, Chris “Kazi” Rolle, Cheo Tyehimba, Dasan Ahanu, Ulester Douglas, Sulaiman Nuriddin,

Rev. John Vaughn, Ras Baraka, Rev. Tony Lee, Lasana Hotep, Timothy Jones, and David Miller, among many others.

Our goal is to not just talk about the problems so poignantly described in the New York Times article.

At this stage we know what they are. Our intent is to create a holistic working conference where we offer

strategies and models for Black male development that already exist, like Men Stopping Violence in Atlanta, or The Brotherhood/SisterSol

here in New York, and how we can duplicate those models to impact very vulnerable Black males nationwide. If we do not do

it, then who will?

Kevin Powell, writer and activist, is the author of Who's Gonna Take The Weight? Manhood,

Race, and Power in America, and the forthcoming essay collection, Someday We'll All Be Free.

You

can email Kevin Powell at kepo1@aol.com

'I have to die a man or live a coward' -- the saga of Dr. Ossian Sweet

By Patricia Zacharias / The Detroit News

"I have to die a man or live a coward." With these words, a mild-mannered black Detroit physician

set in motion forces that would result in a dramatic milestone in America's civil rights movement, extending the notion that

a man's home is his castle to blacks.

It began in the summer of 1925 when Dr. Ossian Sweet decided to move his wife and baby daughter from

the crowded lower east side black ghetto into an all-white neighborhood at Garland and Charlevoix.

Dr. Ossian Sweet

Dr. Ossian Sweet

|

"He wasn't looking for trouble," Dr. Sweet's brother Otis, a dentist, recalled. "He just wanted to

bring up his little girl in good surroundings."

The surroundings may have been good, but they were dangerous for blacks. Sweet knew the risks. Just

a few months earlier, another black physician, Dr. A.L. Turner, had moved into an all-white west side neighborhood on Spokane

Street. A mob invaded his home, moved all his furniture into a van and drove him out of the neighborhood.

"This made a profound impression on my brother," continued Otis. "It was then that he told me he was

prepared to die like a man."

By 1925, Detroit's black population was nearly 80,000. Blacks had migrated to the Northern industrial

cities in search of better jobs. Most were packed into a near east side area called Paradise Valley, or Black Bottom. The area was badly overcrowded -- seven percent of the city's population was squeezed into one percent of its housing. Some

residents slept on bar pool tables and lived four families to a flat.

Dr. Sweet, and his wife, Gladys, wanted something better.

Gladys Sweet

Gladys Sweet

|

Born in a small inland Florida community, Ossian Sweet studied medicine at Howard University, practiced

briefly in Detroit, then continued his studies in Vienna and Paris. Upon his return to Detroit in 1924, he accepted a position

at Detroit's first black hospital, Dunbar, and began saving for a home. By the spring of 1925 he had saved enough to purchase a home on Garland for $18,500 with a down

payment of $3,500 cash.

Rumblings of trouble began well before Ossian Sweet took occupancy of the house. An organization called

the "Water Works Improvement Association" vowed to keep blacks out of the neighborhood.

The woman who sold Dr. Sweet the house told him that she had been warned by a phone caller that if

he moved in, she would be killed along with the doctor and the house would be blown up. Ironically, she and her light-skinned

black husband had lived in the house undisturbed, the neighbors apparently unaware of her husband's heritage.

On Tuesday, Sept. 8, Dr. Sweet arrived at his new home with two small vans of furniture. He also brought

along guns and ammunition and had arranged for friends and relatives to stay with him for the first few days. They included

brothers Otis and Henry, 21, a student at Wilberforce University, John Latting, and William Davis, a federal narcotics officer

who had been an army captain overseas during World War I. All were black.

Throughout the day tensions rose in the neighborhood. The Detroit Police Department regarded the situation

as grave enough to post officers there day and night.

Famed attorney Clarence Darrow headed the defense team. Famed attorney Clarence Darrow headed the defense team.

|

On the following day, Dr. Sweet attended to his practice downtown and most of the others in his home

also went to their jobs. When he returned that night, Dr. Sweet had recruited more friends to join those in the house, bringing

the total to 11 including Mrs. Sweet.

"The street was a sea of humanity," Otis recalled. "The crowd was so thick you couldn't see the street

or the sidewalk. Just getting to the front door was like running the gantlet. I was hit by a rock before I got inside."

The prosecution later produced a series of witnesses who swore that there never were more than 25

or 30 persons in front of the Sweet home.

About 10 p.m. a series of shots rang out from the Sweet home. Leon Breiner, who lived across the street,

fell dead and another man was wounded. Police rushed in and arrested everyone in the Sweet house, charging them all -- including

Mrs. Sweet -- charged with murder.

The NAACP promised to defend Dr. Sweet, his wife and friends and brought in Clarence Darrow, a titan

of the American bar for more than three decades, as chief counsel. His assistants included Arthur Garfield Hays, one of the

nation's leading liberal lawyers, and Walter M. Nelson, a Detroiter.

Presiding over the trial would be a young redheaded judge named Frank Murphy, who would go on to become

mayor of Detroit, governor of Michigan, U.S. Attorney General and a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Afterward Murphy said, "This was the greatest experience of my life. This was Clarence Darrow at his

best. I will never see anything like it again. He is the most Christ-like man I have ever known."

The facts in the case were relatively simple: Someone in Dr. Sweet's house fired a shot that killed

Leon Breiner. Another neighborhood resident, Erik Hofberg, received a bullet in the leg.

Judge Frank Murphy presided over the trial and, in his charge to the jury, made it clear that the right to defend one's

home applied to blacks as well as whites. Judge Frank Murphy presided over the trial and, in his charge to the jury, made it clear that the right to defend one's

home applied to blacks as well as whites.

|

But the issue was far more complicated: Had there been justification for firing that shot?

In his book "Let Freedom Ring," defense attorney Hays left a graphic memoir of the case. "Colored

people regarded the case as one which raised the definite question of race segregation. The claim was made that the shots

were fired in defense of the home. It was pointed out that in Detroit, the Negro population had vastly increased in numbers;

that Negro districts had become congested and were centers of filth and squalor; that it was almost impossible for a Negro

to obtain a decent home except in a white neighborhood; that the whites were always hostile and the colored man was ordinarily

either compelled to move or to use force to protect himself."

Hays, however, conceded in his account of the trial, "On the face of it, our case was not strong.

It seemed clear that Breiner had been killed by a fusillade from the house. Ten men had gathered there with provisions to

withstand a possible siege, with guns and ammunition. And there had been police protection."

The defense, as Hays saw it, depended on the attitude of the defendants at the time of the shooting.

Did they think they were in danger? Were they actually scared? Not all of the defendants cared to admit they were scared.

They had become heroes to the black community.

The prosecution, meanwhile, had formed its own theory of the case. Lester Moll, chief assistant to

Prosecutor Robert M. Toms, recalls "The case had come to the attention of our office 24 hours before the actual shooting.

Phone threats to the Sweets had been reported and a police guard had been posted. The following night shots were fired simultaneously

from the Sweet home. Mr. Breiner was hit while on the porch of a house across the street. The shooting appeared to follow

a pre-arranged signal from within the Sweet home."

"We interviewed police who were in agreement that the crowd out in front was not numerous and that

there was no threat of violence. Based on these conversations we issued a warrant on the theory that the shots were fired

without provocation."

A Detroit News reporter, Philip A. Adler, testified for the defense. He was at the scene of the shooting

and told of a "considerable mob" of between "400 and 500," and stones hitting the house "like hail."

"I heard someone say, 'A Negro family has moved in here and we're going to get them out'," Adler testified.

"I asked a policeman what the trouble was and he told me it was none of my business."

The defense hammered hard at the purpose of the Water Works Improvement Association and its goal to

keep blacks out. In 1925 the Ku Klux Klan claimed 100,000 members in Detroit and a cross had recently been burned at the steps

of city hall.

Detroit News reporter Philip A. Adler testified he saw a mob of about 400 to 500 outside the Sweet home and that rocks

were hitting the house "like hail." Detroit News reporter Philip A. Adler testified he saw a mob of about 400 to 500 outside the Sweet home and that rocks

were hitting the house "like hail."

|

Darrow stressed the state of mind of those huddled inside the Sweet home that night. The emotional

climax of the trial came when Darrow called Ossian Sweet to the stand in his own defense.

Sweet told of seeing a menacing crowd outside his home: "Frightened, after getting a gun I ran upstairs.

Stones were hitting the house intermittently. I threw myself on the bed and lay there awhile, perhaps 15 or 20 minutes- when

a stone came through the window. Part of the glass hit me."

"What happened next?" asked Darrow.

"Pandemonium -- I guess that's the best way to describe it--broke loose inside my house," replied

Sweet. "Everyone was running from room to room. There was a general uproar."

"Somebody yelled, 'There's someone coming.' A car had pulled up to the curb. My brother Otis, and

Mr. Davis got out. The mob yelled, 'Here's niggers, get them! Get them!' As my brother and Davis rushed inside my house, a

mob surged forward. It looked like a human sea. Stones kept coming, faster. I was downstairs. Another window was smashed.

Then one shot, then eight or 10 from upstairs, Then it was all over."

Then came Darrow's key question: "What was your state of mind at the time of the shooting?"

Sweet replied, "When I opened the door and saw the mob, I realized I was facing the same mob that

had hounded my people throughout its entire history. In my mind I was pretty confident of what I was up against. I had my

back against the wall. I was filled with a peculiar fear, the fear of one who knows the history of my race. I knew what mobs

had done to my people before."

Under Darrow's skillful sympathetic question, Dr Sweet told of the terrible legacy of fear that mob

violence had left with his race. Over the protests of the prosecution, his testimony was admitted as having a bearing on the

psychology of the occupants of the Sweet home.

The second jury took only four hours to find Henry Sweet, brother of Dr. Sweet, not guilty. The second jury took only four hours to find Henry Sweet, brother of Dr. Sweet, not guilty.

|

In his closing arguments to the jury, Darrow questioned whether it was possible for 12 white men (however

hard they tried) to give a fair trial to a Negro.

He argued, "The Sweets spent their first night in their new home afraid to go to bed. The next night

they spent in jail. Now the state wants them to spend the rest of their lives in the penitentiary....There are persons in

the North and South who say a black man is inferior to the white and should be controlled by whites. There are also those

who recognize his rights and say he should enjoy them. To me this case is a cross-section of human history. It involves the

future and the hope of some of us that the future will be better than the past."

In his charge to the jury Judge Murphy indicated clearly his belief that a man's home is his castle

and that no one has a right to invade it. He left no question of the right to shoot when one has reasonable grounds to fear

that his life or property is in danger. And he made it clear that these rights belong to blacks as well as to whites.

The jury deliberated for 46 hours, then announced that it had been unable to reach a verdict. The

prosecution was not ready to give up, and elected to press charges against a single defendent, Henry Sweet, the 21-year-old

brother of Ossian. The state believed he fired the shot that killed Leon Breiner. The second trial in many ways paralled the

first. The testimony remained almost unchanged and Darrow again gave a moving summation.

Prosecutor Robert M. Toms Prosecutor Robert M. Toms

|

After reviewing the horrors of the slave ships and the two centuries in bondage in the United States

that Black Americans had endured, Darrow declared that they were owed a debt and obligation by the white race.

He went on: "Your verdict means something in this case. It means something more than the fate of this

boy. It is not often that a case is submitted to 12 men where the decision may mean a milestone in the history of the human

race. But this case does. And I hope and trust that you have a feeling of responsibility that will make you take it and do

your duty as citizens of a great nation, and as members of the human family, which is better still."

The jury found Henry Sweet innocent after less than four hours deliberation. No further effort was

made to prosecute any of the defendents.

After all charges were dropped against him, Ossian Sweet moved back into his home on Garland.

However, tragedy plagued his later life. Not long after his brother's trial, Dr. Sweet lost the family

he had purchased the house for in the first place. His daughter, Iva, died of tuberculosis in 1926, at the age of 2. His wife,

Gladys, succumbed to the same disease soon after. The widow of Leon Breiner, shot on Garland Street, sued for $150,000 but

the case was dismissed. Dr. Sweet tried his hand at politics, running four times for various offices, but losing all. He remarried

twice, both marriages ending in divorce.

In 1944, he sold the house on Garland and purchased a pharmacy where he lived above the store. In

1960, after years of ill health and depression, he was found dead, a bullet through his head and a revolver in his hand.

The Sweet home as it looks today. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enter supporting content here

|

|

|

|